By Dr Joan Latchman

CJ Contributor

BIG, DAMAGING earthquakes are an important part of the written history of the Eastern Caribbean, which began with Europeans in the region.

In bringing their architecture with them, the vulnerability of the region to geological hazards was dramatically demonstrated, with the first such disaster on 5th April, 1690, when an earthquake, near St Kitts and Nevis, caused the collapse of some buildings in Antigua, with associated fatalities; ground failure in St Kitts, with some sugar mills being buried and landslides on Nevis Peak; there was also a tsunami observed in Charlestown, Nevis; there was like damage in Guadeloupe.

This is worthy of note, because unlike other regions of the world, where there are fantastic accounts of tremendous devastation from earthquakes that were considered myths until a repeat in modern times, no such accounts appear to exist in the oral tradition of the Eastern Caribbean.

However, the historical accounts, through the 17th – 19th Centuries, should be sufficient proof of that vulnerability, in spite of the less severe earthquake impact seen in the 20th Century.

Earthquake and volcanic activity in the Eastern Caribbean arise from the sinking of the North American plate beneath the Caribbean plate, a process known as subduction.

The plates converge at the slow rate of 2 cm per year, which is about the rate, at which fingernails grow.

This slow rate is responsible for the long interval between the region’s biggest earthquakes and allows for the attitude of complacency that exists among the peoples of our region and the absence of urgency in ensuring that our systems to address these hazards are at full strength.

The Lesser Antilles arc is the eastern boundary of the Caribbean plate.

Such plate boundaries are comprised of a system of faults of varying sizes.

As the plates converge, frictional forces resist that motion and strain energy accumulates on the faults making up the system.

The small faults, in the system, can accommodate only a small amount of strain before they move and such movements produce the small earthquakes that are recorded daily, in the region.

Bigger faults can hold more strain energy and they move on timescales of weeks, still larger ones, months, bigger than those, years, with the major faults releasing their earthquakes every 20-30 years and the biggest faults, in the system, every 100 or so years.

Some have commented that scientists just say such things to justify their existence.

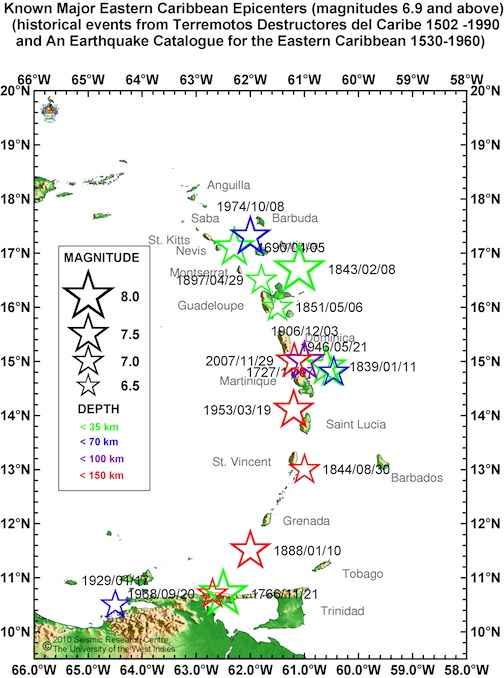

However, while an earthquake on the scale of the biggest earthquakes that have occurred in the region throughout our history has not been seen for more than a century, the major earthquakes have been occurring almost on cue: 1906 and 1946, near Dominica and Martinique; 1953 north-west of Saint Lucia; 1974 north of Antigua and 2007 north of Martinique.

This is important, clear evidence that big faults making up the earthquake generating system, in the Eastern Caribbean, continue to accumulate and release strain energy.

This means that the biggest faults are accommodating the strain energy being received and that one day they will reach their limit.

Given the time since the last such event on 8th February, 1843, at least one such fault should be near its accommodation limit.

The countries making up the Eastern Caribbean invest heavily in development and the overall standard of living is relatively high.

An earthquake on the scale of the one in 1843 can be so devastating for the countries closest to the epicentre that development is setback decades.

In 1843, the highest level damage extended from northern Dominica to Saba.

The lesson to be taken for this is that the largest earthquake will inflict damage across a wide zone; therefore, we ought not to be overly concerned with the exact location of that next great earthquake.

Wherever it occurs in our region, a significant area will be negatively impacted. Fig. 1 shows that while the big earthquakes in our history do appear to have some preferred locations, they also appear to ensure that no zone is left out.

It is for this reason that measures to address the earthquake hazard be expeditiously developed and implemented.

There are national, regional, local and individual measures.

Such measures should address both short- and long-term needs and include development, legislation, implementation and enforcement of building codes; development, implementation and enforcement of land use plans.

Individual response to the earthquake hazard also needs to change. When improved, it would be one of our most important short-term assets.

Dr Joan Latchman is a Seismologist, at the University of the West Indies Seismic Research Centre. For more information visit the SRC’s website here.