By Gerard Best

Op-Ed Contributor

INTERNET USERS are bombarded daily with a vast world of digital content via news feeds, blogs, webcasts, live streams, image galleries, videoclips and sound bites. Access to huge information repositories is no longer restricted by the walls of a library or even the tether of a computer mouse. Mobile broadband internet access and the rapidly growing selection of mobile devices allow us to access content anytime and anywhere. The age of information overload is upon us, and here to stay.

In this age of plenty, newsrooms in the Caribbean and elsewhere find themselves strapped for cash, short on staff and struggling to keep pace. Media owners and executives are perplexed. Many seem unable or unwilling to make the investments required to evolve newsroom operations from the narrow frequency of the traditional, established workflow to the broad bandwidths of multimedia convergence, real-time crowdsourcing and data-driven investigation.

Making meaning

Technology, that unremitting equaliser, is inundating both newsrooms and audiences daily with more data than they can process meaningfully. The leap is not just in quantum but in velocity. Newsrooms face steep learning curves, as consumers’ attention spans shorten, redefining the realistic timeframes of journalistic relevance. Breaking news is a game of quick draw, with amateur and professional reporters alike rushing to online outlets to post and repost prized “first” updates. By the time responsible professionals take the time needed to probe the credibility of emerging allegations, annotate the misinformation going viral on social media, and publish the verified facts, the game is lost. The damage, invariably, is already done.

In such an environment, traditional journalists’ bread and butter of gathering and disclosing verified facts is surfeit; what consumers crave is not just information but knowledge, not simply content but context. Which means journalists’ core function is no longer simply to inform but to impart understanding. Enter the data journalist.

Making meaningful change

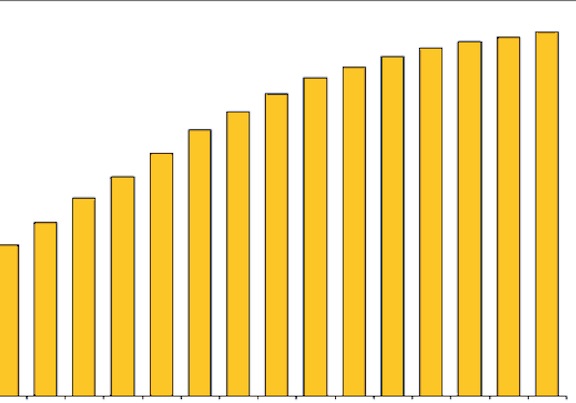

But what is data journalism and how is it different to the rest of journalism? At its core, data journalism (or data-driven journalism) is based on analysing large or small data sets for the purpose of creating news stories and meaningful visualisations. The process builds on the availability of open data and often relies on open source tools. Significantly, data-driven journalism is often associated with public service, thrusting journalists into a new kind of relevance for society. The various platforms involved with this type of reporting open doors for reaching a broader and more varied audience.

The data journalist interrogates human sources but also wrenches vital information from reluctant databases and tight-lipped spreadsheets. Data journalists could just as easily be called beta-journalists: they are a prototype of what mainstream newsrooms desperately need, and they value experience as much as experimentation. Experienced media professionals who do not cultivate the intellectual curiosity to embrace the data journalists’ ethos of continuous innovation and adaptation will see their combined decades of experience, once an asset, become a fatal weakness.

Yet, never have the core values of traditional journalism–accuracy, completeness, honesty, transparency, impartiality and relevance–been more needed. Like development journalists, data journalists must develop robust ethical frameworks to guide their editorial decision-making. Given their orientation to public service issues, they should frame editorial decisions on at least four levels—individual, organisational, institutional and social—to ensure that a broad range of considerations shape content.

No silver bullet

Data journalism is no panacea. It will not sweep away the grim economic choices facing courageous, hard-working, self-respecting journalists, bloggers and other new media practitioners across the Caribbean, or anywhere else for that matter. In fact, working with data has challenged journalists in Europe, Latin America, North America and Africa to rise to new levels of enterprise and ingenuity.

As Paul Bradshaw cautions, “Data can be the source of data journalism, or it can be the tool with which the story is told—or it can be both. Like any source, it should be treated with scepticism; and like any tool, we should be conscious of how it can shape and restrict the stories that are created with it.”

Amateurs and professionals alike can and should learn to produce data stories quickly and effectively and discover how to transform data into simple, compelling and informative visualisations. Gaining the highly demanded data analysis and presentation skills that are necessary for many data journalism jobs today will empower Caribbean newsrooms to find new relevance amid the changes now transforming the global media landscape.

Gerard Best is New Media Editor at Guardian Media Limited, Trinidad and Tobago. This article is adapted from a presentation originally delivered at the Trinidad and Tobago Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and BrightPath Foundation open data workshop in Port of Spain, Dec. 12, 2013.

Note: the opinions expressed in Caribbean Journal Op-Eds are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Caribbean Journal.