By Alexander Britell

NASSAU – At Nassau’s Vincent D’Aguilar Art Foundation, a gallery that is one of the great new spaces of the quickly-growing Bahamian arts scene, Haitian artist Chantal Bethel is producing “Poto Mitan,” a three-dimensional production of work she created in an attempt to find healing after the earthquake in Haiti. Bethel, who fled Haiti during the Duvalier regime, has created a vivid show across all media – from sculpture to painting. To learn more about her and the work, Caribbean Journal talked to Bethel about Poto Mitan, the relationship between Haiti and the Bahamas, and how the two countries influence her work.

What brought you to do this show?

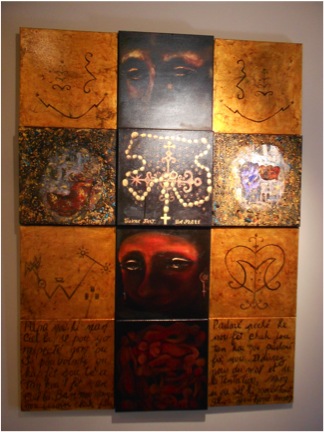

I grew up in Brussels, and I’ve been living in the Bahamas since 1971, which is quite a long time. This was etched in my memory for a long time after the earthquake happened. I decided that I needed to make art – that was my way of dealing with it. And the first piece I actually did is not here – it was acquired by the Haitian Embassy in Washington. After that, I decided I should do a whole body of work. The first piece was “Poto Mitan,” which are the words for “Pole” and “Middle,” which is usually the centre of a voodoo temple and has the same connotation as the tree of life, which is the place where heaven meets earth in the voodoo religion. I decided to go there because voodoo is something I was always afraid of – as a child, when I grew up, it was taboo in my family. I was raised as a Roman Catholic. So I met a Haitian artist who lives in Florida, [Edouard] Duval-Carrie. He presented the Haitian mythology in a very nice way – he had a talk [in Nassau] and said that since all the Haitians are leaving Haiti, the gods should leave as well, so he put them on a boat and sent them to Miami. So you saw the goddess of love in Miami Beach [in his work], so it gave me a different feel. I wanted to explore the voodoo religion, which is not the voodoo like it is presented by Hollywood, like black magic.

The first piece was “Poto Mitan,” which are the words for “Pole” and “Middle,” which is usually the centre of a voodoo temple and has the same connotation as the tree of life, which is the place where heaven meets earth in the voodoo religion.”

This is the actual African religion, which, in the 16th century, when slaves were brought into Haiti, they were not allowed to practice the religion, because the priests wanted them to convert them into the Christian religion. So they hid behind the Catholic saints – so you see a lot of Catholic connotations here [in my work], like the rosary on some of the works, and then something voodoo. So there is a mixture of the two religions – they blend the two very well. So I decided to use a sacred space and to pray for Haiti – this is a prayer for Haiti.

How much does Haiti influence your work?

I am told that you can see Haiti in my work. But sometimes it looks very Bahamian. In this particular body of work, Haiti is very strong, because of what I’ve used – I’ve been inspired by the voodoo religion, using all of the masks. The calabash, which is a very spiritual fruit in many religions, in Haiti is used by a lot of people to carry water to drink. And the calabash is actually a gourd – which is why the Haitian currency was named for a gourd by King Henri-Christophe – and that’s why I’ve used it in this show because it’s very strong in Haiti.

How much does the Bahamas impact your art?

What I learned is that when I do work about Haiti, the colours seem to be darker. And when I do work about the Bahamas, I use a lot of pastel colours, so this probably shows what Haiti meant for me – having left under the Duvalier regime my father was exiled and all of that, all the misery in Haiti – so the Bahamas is more like a paradise. So the colours actually show you the difference – when I’m painting the Bahamas and when I’m painting Haiti.

How would you describe the relationship between the two countries?

There is a strong relationship. There is a big problem in the Bahamas because there are so many illegal immigrants that come to the Bahamas, and that poses a big problem for the Bahamas. But I think that the Bahamas and Haiti have been working together for a long time. When things are good in Haiti, there is a lot of business between the two countries, and there are a lot of people of Haitian origin in the Bahamas – including me! So it’s good.

The colours actually show you the difference – when I’m painting the Bahamas and when I’m painting Haiti.”

Moving into art was something of a career shift for you.

It’s an interesting story, because I studied business administration, and I worked as a financial comptroller for many years, and the story is that I never felt totally fulfilled with what I was doing. I remember, in 1992, I was going to have surgery, and I was talking to my doctor, and he said, “why don’t you try doing something you like to do?” I used to dabble here and there, and do drawings, so I decided I would start painting. The first work I did was a painting of his house, and I gave it to him, and decided at that point that I was going to go into art – but I was also working as a financial comptroller. So for almost 10 years, I was doing art part-time and accounting full time. And then I decided I was going to give up accounting figures for art figures.

What are you working on now?

Well, I’ve been working on this show for two years. And right now, my studio is absolutely empty except for two pieces I’m working on with fiber. There is a show that will be produced in two months, “Transforming Spaces,” and it’s going to be during the month of March, where I do sculptures with the royal palm tree, and that’s my fiber.